There has recently been a very interesting case to come out of Africa that deals with the persistent refusal of the Kenyan government to recognize the nationality of a minority group that has been present in the country for almost a century. The case,

Nubian Minors v. Kenya, was brought to the African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (

ACERWC) by the

Institute for Human Rights and Development in Africa along with the

Open Society Justice Initiative. The ACERWC is an institution that deals with interpreting and deciding on issues related the OAU's

African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, Africa's answer to the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Like the CRC, the African Charter provides explicit nationality and legal personality rights for children. Article 6 requires that every child is entitled to a name, a nationality, and birth registration. Further, children who would otherwise be stateless are entitled to the nationality of the country in which they are born. The Nubian Minors case was brought under these provisions, along with the non-discrimination clause and several other collateral clauses.

|

| Nubians from KAR |

The Facts

The story of the

Nubians of Kenya is old and interesting. Apparently, this group came from the Nuba mountains in present-day Sudan, and were forcibly conscripted by the British in the 19th century into the

King's African Rifles. After service, they requested to be sent back to Sudan, but were instead allocated land in Kenya, namely,

Kibera, right outside of present-day Nairobi. Next best thing, right? Wrong.

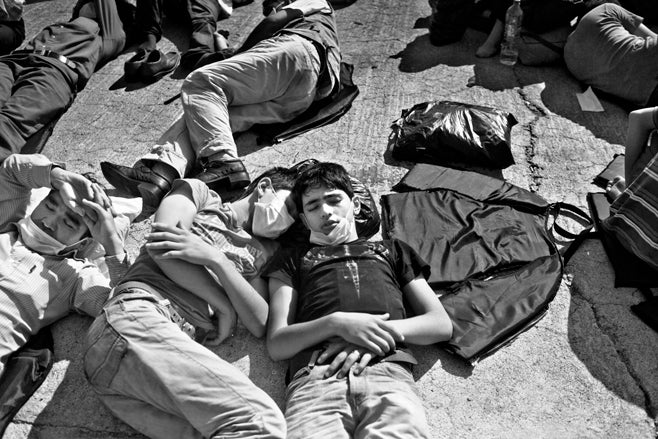

Now here is the tricky part: having been moved to Kenya, most of these people held no Kenyan citizenship. The British also refused to grant citizenship. At the time of Kenyan independence, in 1963, nothing about the Nubians was settled- they were still considered aliens by the government, who also refused to recognize Nubian title to the Kibera settlement. To make matters worse, these status problems were passed by the Nubian Kenyans down to their children. It is allegedly difficult in Kenya to register children in the absence of the parent's identity documents (which as we know, many people of Nubian descent do not possess.) And other human rights organizations have noted discriminatory practices in birth registration, such as refusing to issue a birth certificate. Further, children in Kenya do not receive proof of citizenship until the age of 18, at which point many children of Nubian descent find the fairly straight-forward procedure to verfiy their nationality complicated by discriminatory procedural barriers and delays. The result? Generations of legally invisible and de facto stateless people.

The Case

After considerable efforts to obtain remedies at the state level (see section 15-22 of the

Decision) the applicants were able to have the case heard on the merits. The first issue the Court considered is whether the ACRWC grants citizenship from birth. While the reading of art. 6(1) doesn't provide a right from birth, taking into consideration the best interests of the child principle, this is a logical reading. Further, statelessness is particularly devastating for children.

Whatever the root cause(s), the African Committee cannot overemphasise the overall negative impact of statelessness on children. While it is always no fault of their own, stateless children often inherits an uncertain future. For instance, they might fail to benefit from protections and constitutional rights granted by the State. These include difficulty to travel freely, difficulty in accessing justice procedures when necessary, as well as the challenge of finding oneself in a legal limbo vulnerable to expulsion from their home country. Statelessness is particularly devastating to children in the realisation of their socio-economic rights such as access to health care, and access to education. In sum, being stateless as a child is generally antithesis to the best interests of children. (at 46)

Having said that, the Committee considered several possible arguments by Kenya. First, the fact that some Kenyans of Nubian descent had acquired citizenship through the normal legal procedure. The Committee considered that this did not destroy the central argument, that a significant portion had not, which would be enough to violate their obligation. Second, Kenya could have argued that the Nubian children may be entitled to Sudanese citizenship. In this case, the Committee responded, the government could have tried to cooperate with Sudan to facilitate such granting of nationality, but there was no evidence that they had done so (at 51). In sum, they had violated their obligation to provide children with nationality, birth registration, and to help them avoid statelessness, all in violation of the key provisions of Article 6.

As to the discrimination claim under ACRWC art. 3, the Court found prima facie discrimination. The government's absence made it impossible for them to meet the burden of proof with evidence that the discrimination served a legitimate end, however the Court looked for explanations, and in the end relied on findings by the Kenyan National Commission on Human Rights, that

“the process of vetting… Nubians… is discriminatory and violates the principle of equal treatment. Such a practice has no place in a democratic and pluralistic society” (at 56)

In the subsequent paragraphs the Court found that these violations also deprived the Kenyan children on Nubian descent of their right to health and their right to education. In other words, positive findings on all fronts for the applicants.

Follow Up

Of course, it remains to be seen what the impact of the case will actually be on affected communities. Kenya was instructed to come up with an implementation plan, which would have to include some legal mechanisms to register extant stateless minor Nubians as Kenyan, as well as a method of birth registration and subsequent acquiring of citizenship that is non-discriminatory and functioning.

In the meantime, lawyers have some excellent new case-law. This case speaks to, specifically:

- the fact that statelessness is not "in the best interests of the child"

- the link between birth registration and preventing statelessness

- the impact of statelessness and legal invisibility on the ability of a child to access his health and education rights

- additional barriers to birth registration and citizenship on the basis of ethnicity/ origin of parents can constitute discrimination.

All in all a big win, and a situation that lawyers interested in statelessness and legal invisibility will definitely want to keep an eye on.